What is an idea?

demystifying the idea of an idea

What is an idea?

We have a tendency to overcomplicate the idea of an ‘idea’. If asked, ‘what is an idea?’, people often answer with reference to something ‘inside our heads’ or in terms of ‘a thought’, and so on. But I think that the field of education would benefit if we demystified the notion somewhat.

I think the most straightforward way to understand an idea is as a tool, a tool for thinking. An idea is something that we use to compare, discriminate, classify, order, assimilate etc. the things we wish to think about.

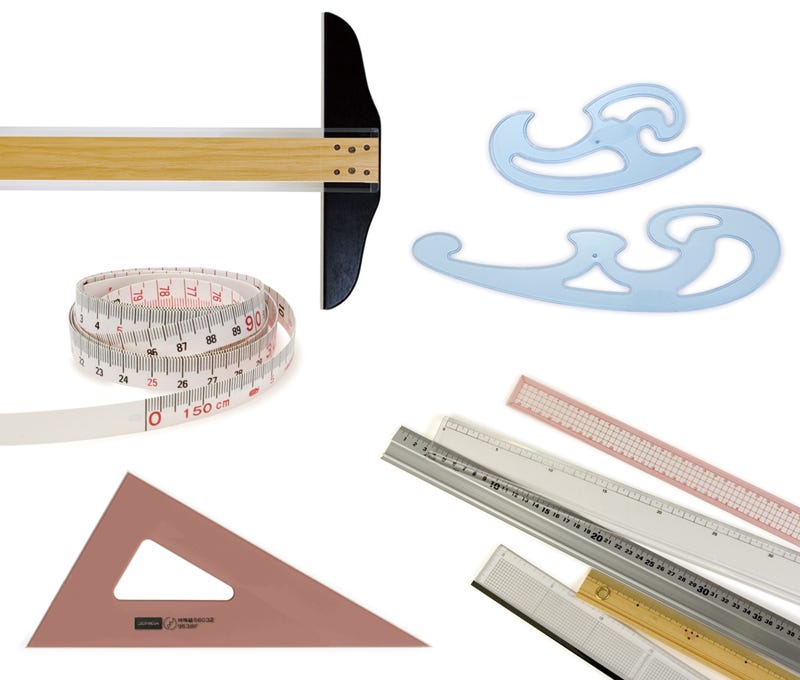

An idea is a tool just as a ruler or a protractor is a tool. We use rulers to compare, discriminate, classify things, and we do the same with ideas.

But a ruler is made of plastic, metal, or wood. What is an idea made of? —again, we are tempted to think that ideas are made up of something mystical like ‘thoughts’, but this is a mistake.

Just as a ruler is a plastic, metal, or woord structured in particular ways, an idea is a set of sounds, words, gestures, images (etc.) structured in particular ways. The genius of language is that we managed to create tools using nothing more than the noises and marks that we make.

We normally define, explain, give the rules for the expression of ideas with words and gestures. A sentence like ‘triangles have three sides’ might look like a description of triangles, but it’s actually just a rule, or better a norm —a norm of representation.

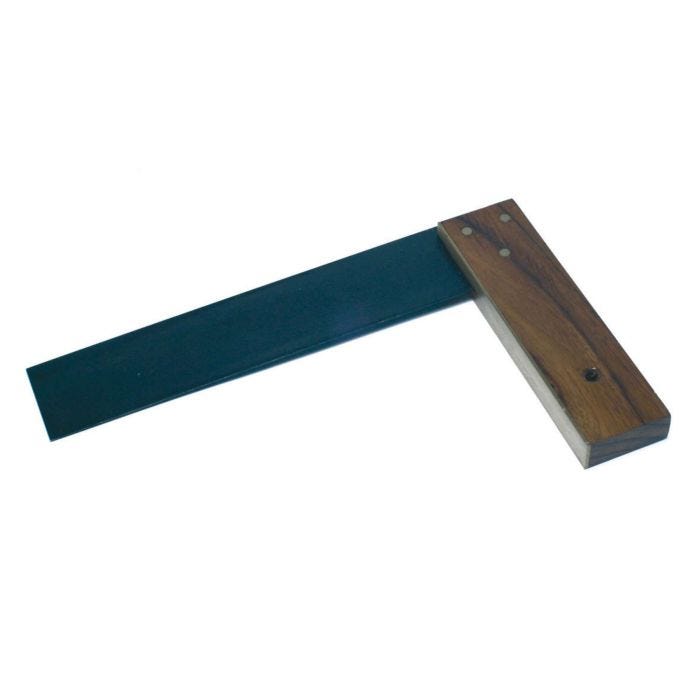

The word ‘norm’ comes from the latin word ‘norma’ meaning a carpenter’s square. And ‘norma’ comes from the greek ‘gnomon’ (γνώμων) which comes from the word ‘gignosco’ (γιγνώσκω) meaning to know. A carpenter’s square is a knower, a discerner —a tool for comparing, discriminating, etc.

If we think of any norms of representation, for example, ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5…’ or ‘triangles have three sides’ we can see how they might be tools for comparing, discriminating, ordering things.

But this also shows us a further complication for teachers: it’s not enough that a student can construct the norm, they also have to be able to use it and apply it. Children learn to count (construct the norm) before they learn to apply it (and actually count objects, for example).

Someone can’t really be said to possess a concept, to have power over it, until they’ve mastered its application.

Let me know what you think of this account.