"Predictive Processing" is a zombie-ant fungus

(This post is written in response to Adam Wray who argued here that Predictive Processing could explain the difficulties with Engelmann’s theories of instruction.)

Found in tropical rainforests, there is a fungus known as Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. This fungus infects foraging ants through spores that penetrate the ant’s exoskeleton and slowly take over its behaviour.

As the infection advances, the ant is compelled to leave its nest for a more humid microclimate that’s favourable to the fungus’s growth, where it will find a spot about 25 cm off the ground, bite into a leaf, and wait for death.

Meanwhile, the fungus feeds on its victim’s innards until it’s ready for the final stage. Several days after the ant has died, the fungus sends a fruiting body out through the base of the ant’s head, turning its shrivelled corpse into a launchpad from which it can jettison its spores and infect new ants.

The idea of Predictive Processing (like other ‘information processing’ frameworks) is the conceptual equivalent of this zombie-ant fungus. It’s a piece of nonsense that, in order to propagate itself, infects every concept around it, eating it from the inside, making it behave in weird ways, until it finally dies.

The basic idea

“Predictive processing (PP) is a framework involving a general computational principle which can be applied to describe perception, action, cognition, and their relationships in a single, conceptually unified manner.”[1] That general computational principal is to treat the brain is a hierarchical inference engine whose sole objective is to minimize “prediction error” (surprisal) by matching its internal models of the world to incoming sensory data.

Initial site of infection: perception

The origins of PP can be traced back to the work of Hermann von Helmholtz, who believed that he could explain various visual illusions as mistaken ‘unconscious inferences’. Helmholtz believed that the stimuli from the eyes were transmitted to the brain where they became sensations, and the unconscious mind synthesizes these sensations, forming hypotheses about what’s out there in the world. Illusions are, according to this theory, caused by the failure of our inferences and hypotheses to line up with the world.

However, this doesn’t, however, make any sense. A hypothesis is a supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation, and that isn’t what is going on when I see a chair in front of me. Yes, a prerequisite of my ability to see a chair is that I have functioning eyes and that I know what a chair is, but I’m not supposing that this is a chair, or proposing that it’s a chair. That’s just nonsense.

In order to attempt to shoehorn perception into this prediction-shaped box, the PP-er could, like some pseudo-Descartes, try to claim that I might be wrong about whether or not I see a chair in front of me. Perhaps it’s just an illusion!

But if it turned out that it wasn’t a chair after all, then I didn’t actually see a chair to begin with. I was seeing something else— maybe a box, or maybe I wasn’t seeing anything at all and just experiencing a hallucination. The fact that I might be mistaken doesn’t mean that my initial thought was a prediction. Think of how we might differently sit on a chair if we were only supposing that it was a chair. I would carefully lower my arse onto it, not fully allowing it to take my wait until I was confident. That isn’t how we ordinarily sit on chairs.

In my previous post, I argued that the checkerboard ‘illusion’ was actually just the result of applying different norms or circumstances to the image rather than the result of a failed hypothesis. Adam Wray makes the following objection to this:

“A particularly revealing feature of the illusion is that it cannot be undone by a conscious change of intent or norm. Even when we explicitly try to operate under a different rule set, for example by telling ourselves that the task is to identify squares of exactly the same colour, perception remains locked into the checkerboard pattern of light and dark squares. Knowing the correct answer does not change how the image appears.”

Firstly, my point was that what counts as ‘the correct’ answer is actually normative (something we’ll come onto in a moment, as PP-ers can’t actually make any sense of ‘correct’).

Secondly, the final sentence here is a muddle. No, of course applying different norms to an image doesn’t change how it appears — because I’m not changing the image! But it might change how we understand the image. If I were painting the checkerboard illusion, I’d know to paint the two squares the same colour.

Norms and rules are obviously relative to certain contexts and circumstances. There’s nothing mysterious about this. And it’s absolutely true that we might make mistaken assumptions about the circumstances of an image. But again, an assumption isn’t a hypothesis. To assume something (in this sense) is to take it for granted without questioning it. This is fundamentally different from hypothesising, which forms the basis of further investigation.

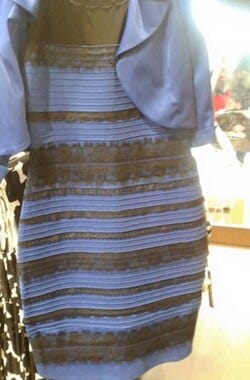

When I first looked at “the dress” illusion, for example, I assumed that the light source was in front of the dress (making me comprehend it as white and gold) but I am perfectly able to correct that assumption and comprehend the light as shining directly onto the back of the dress (and correspondingly makes me comprehend the dress as blue and black).

Zombie-knowledge

I suppose that a reason why people might think this idea has legs is that on some very narrow occasions, ‘I know…’ is synonymous with ‘I can make decent predictions about things relating to…’. For example, ‘I know my students’ is (in some senses) synonymous with ‘I can make decent predictions about my students’.

What’s conceptually interesting about PP is that in most western languages, there are two words for to know: one etymologically related to the senses, and one etymologically related to the proto-indo-european root *ǵneh₃-.

In Spanish, for example, the two words are saber, and concocer. Saber comes from a word meaning ‘to taste’. In English, we now only have the word know (which comes from *ǵneh₃-) but we still have remnants of wit which ultimately comes from a word meaning to have seen (in the perfect tense).

The difference between the two senses is between what one has experienced, and what one has insight into or understanding of.

So, for example, ‘I know that she went to the shops’, could be synonymous with…

I heard that she went to the shops.

I saw that she went to the shops.

Sometimes people seem to think that ‘acquaintance’ knowledge (e.g. I know London) is more superficial than the ‘propositional’ knowledge described above, but that isn’t born out by how we ordinarily use words. ‘I know Geoff’ tends to mean something like…

I am familiar with Geoff.

I have some understanding of Geoff.

I have some insight into the nature of Geoff.

Perhaps this stems from the distinction between a person being a mere ‘acquaintance’ rather than ‘a friend’. But if we were asked ‘do you know Geoff?’ and we had literally only met him, then we would reply, ‘well I met him once, but I don’t really know him’. To know something in the sense of being familiar with it is to have done more than just experienced it. It is to have applied some thought, some norms and ideas to it, and so to know-one’s-way-around it. So in that sense, I suppose that the PP’s conception of ‘knowing’ is more like acquaintance rather than propositional or ability knowledge.

All that said, there are loads of ways in which ‘I know…’ is not synonymous with ‘I can make decent predictions about…’ I’ll quote Wittgenstein: “A main cause of philosophical diseases”, wrote Wittgenstein, is “a one-sided diet: one nourishes one’s thinking with only one kind of example.”

‘I know how to spell my name’ doesn’t mean that I can make predictions about how to spell my name. Spelling my name doesn’t involve predictions. Neither does counting or adding etc. I might use that knowledge to make some predictions - e.g. if someone has a name that sounds like ‘Bernard’ I might predict that it’s spelt similarly. ‘Knowing that a square has four sides’ is not a matter of ‘predicting’ that, if I come across a square it will have four sides.

Again, we might get drawn into the tortuous game of trying to shoehorn all knowing into our prediction-shaped box. Imagine I say that ‘I know where a supermarket is, I’ll go’. The PP-er might say something like,

—‘if you walk down to the supermarket, then you are predicting that the supermarket is in a particular place’.

And then I’d argue that that’s not true, because I know that the supermarket is where it is.

—ah but the supermarket might not be there!

At this point the PP-er again becomes pseudo Descartes attempting to find doubt where there is none. The fact is that doubting that the supermarket (which is two minutes from my house) has disappeared overnight, simply isn’t a reasonable belief. And even if it weren’t there, that wouldn’t make my statement ‘I know the supermarket is there’ a prediction, it would just mean I was wrong — I didn’t know after all.

If the PP-er really wants to stick with the idea that my knowing where the supermarket is is a prediction, then they’ve radically changed the meaning of the word ‘to know’.

Zombie-understanding

And this happens with the concepts ‘understanding’, ‘believing’, ‘knowing’, and ‘perceiving’ as well. If the PP-er were right, then there would be no difference between any of these as they’d all be different variations on an ability to predict

Adam Wray describes what he calls ‘the uncomfortable truth about “understanding”’.

“From a Predictive Processing and Active Inference perspective, what we call “understanding” is nothing more and nothing less than having an effective generative model. There is no extra mental layer beyond that. There are only predictions, and how accurate those predictions turn out to be over time.”

So for the PP-er, there’s no difference between understanding and knowing, since both can be reduced to ‘having an effective generative model’.

But this seems patently false.

I can know what someone said without understanding it

I can struggle to understand a fact (and struggle to remember it) but there is no such thing as struggling to know a fact.

I can struggle to know whether something is true, but I can’t struggle to understand whether something is true.

I can misunderstand but I can’t misknow —hence I can not understand accurately, correctly, precisely, properly, rightly, but I can’t correctly know something (since there’s no such thing as incorrectly knowing it —know is a factive verb).

I can know my way home, but I can’t understand my way home.

Zombie-truth

And regardless, if the brain were in fact an inference engine, then this could neither be ‘the truth’ nor ‘uncomfortable’, since neither concept would mean anything.

Since all propositions are predictions made as a result of our generative models, we cannot talk about ‘truth’, we can only talk about those predictions which turned out to be false and those which have not as yet.

It’s overreach of any scientific theory to call itself ‘the truth’ in one sense, but it’s even more non-sensical for someone to call PP the truth, since the term has no meaning within its framework.

Zombie-emotions

And since we are now nothing more than machines reacting to things, do we not also have to jettison talk of emotions too? Hence, it can’t really be said to be ‘uncomfortable’.

Zombie-reasons

As with any attempts to describe ‘cognitive mechanics’, PP inevitably reduces reasons to causes.

Imagine a conversation about a student’s progress in your class. What kinds of explanations might we give?

We might re-describe what they did in a way that indicates the manner of her actions: ‘She’s been working really hard’, ‘she’s really been paying attention in class’.

We might explain it in terms of some kind of regularity: ‘She always does well with these kinds of topics’.

We might talk about their motive: ‘She was afraid of getting in trouble’.

We might give their reasons: ‘She just really wanted to get a 9 this term.’

If someone has not done something we might explain it in terms of an inability, lack of equipment or opportunity and so on.

And yes, we might also give causal explanations for actions that are involuntary or only partially voluntary. ‘She shouted out in class because she was hit really hard.’

But we can see that causal explanations are only one kind of explanation amongst many, and we cannot reduce all types of explanations to causes.

The reason why a student does a certain thing is not the cause of their doing it. The student’s reason for writing ‘10’ might be that ‘5+5=10’, but that 5+5=10 isn’t a cause. It doesn’t cause the student to write ‘10’. Their reason for working hard may be ‘so I can get an A’, but ‘so I can get an A’ isn’t a cause. Reasons try to justify actions and behaviour, but causes don’t. And so reasons can be cogent, sound, compelling, convincing, persuasive, weak, sentimental, selfish. Causes can’t be any of these things.

And PP goes even further than this by arguing that the sole objective of our brain is to minimize surprisal, which according to the Free Energy Principle is a measure of how unlikely a sensory state is, given one’s internal model.

So… when I hug my kids it’s because I’m trying to minimise ‘surprisal’.

A PP-er is asked, “why are you crying?”

“Well I think that it’s because I’m sad because my wife has died, but I suppose it must really be because I’m trying to minimise surprisal”.

Zombie-people (well just zombies)

The framework of PP has no way to account for two-way powers — the powers to act or refrain from acting. If learning and knowing is just about building a more accurate model and that causally explains why we do what we do then we cannot act in any way other than how we in fact do.

So a prediction isn’t really a prediction as ordinarily understood, it’s just a reaction. And any description or framework isn’t a description or framework as ordinarily understood either — again these are just nothing but reactions, the results of one-way powers to process information. To mean something by what we say is to intend to say or refer etc. but we can only intend if we can want if we can have purpose. And it can’t make sense to say that a being with only one-way powers wants anything anymore than it would make sense to say that a rock hates being thrown.

So do we have to ditch the notion of free will, and the idea of volitional activity? This would involve ditching things like talking meaningfully, acting intentionally, bravely, justly, with contrition, etc. Is all of this must just an illusion?

The move that enables PP-ers to ignore questions of free-will is because they avoid referring to people at all and instead refer to ‘brains’. It’s not people that predict, it’s brains.

But this is an instance of what PMS Hacker and MS Bennett call the mereological fallacy: the error of attributing psychological properties (like thinking, feeling, or predicting) to a body part (like the brain) that can only logically apply to the whole living organism.[2]

It is the person that hypothesises and predicts not the brain. You can no more ascribe the property of hypothesising to a brain than you can flying to the engine of an aeroplane.

I may require my hands to play the piano, but that doesn’t mean that they play the piano. I may need a brain to predict, but my brain doesn’t predict. Investigating brain injuries tells us that specific parts of the brain enable particular powers. But we must not confuse that which facilitates a power with the power itself. The fact that a car can’t move when a wheel is missing doesn’t make the wheel a means of transport.

Some may argue that this is just harmless metonymy? This would be harmless metonymy or synecdoche were it not for the fact that people also attribute powers to the brain (or mind) that they don’t attribute to the persons. Brains are said to construct, predict, have their own language, want and so on. So it’s not simple metonymy or synecdoche like, ‘he asked for her hand in marriage’. It’s not even zeugma like, ‘he asked for her hand in marriage, which was wearing a glove.’ When we say things like, ‘your brain learns by generating better internal models’, it’s metaphor, upon zeugma, upon metonymy, like ‘He asked for her hand in marriage, which was wearing a glove and wasn’t keen despite the rest of her quite liking him.’ It’s difficult to argue that this makes anything clearer, or explains anything.

Zombie-frameworks

PP has been designed as “a framework involving a general computational principle which can be applied to describe perception, action, cognition, and their relationships in a single, conceptually unified manner.” Yet it what it describes isn’t really any of these things. Yes it is a unified manner, but it’s just because it insists, absurdly, that all these things are just version of predictions

The problem is that PP relies on the concepts that it then destroys – including ‘framework’ and ‘prediction’. PP saws off the branch on which it sits.

What can a ‘framework’ be for a PP-er? If we’re prediction machines, then we can’t really follow rules, we can be programmed to act. A machine can be programmed to execute an algorithm, and as long as it doesn’t malfunction, the causal connections ensure a specific output, but this isn’t following a rule. To follow a rule is a two-way/volitional power. A prediction machine can no more follow rules than can a see-saw.

So what then can be the purpose of this framework, this set of rules, or rubric if we can’t follow it? The framework itself is just the output of a machine, and all we can do is react to it.

Give a small boy a hammer…

I suppose that PP is attractive because it promises that we might be able to simplify that learning down to a handful of simple rules. A silver bullet for the complexities of the job.

The difficulty is that PP simplifies things in the way someone might think that they’ve simplified a car by removing everything except the wheels. It’s just not a car anymore. And what we’re left with after PP has had a go at ‘perception, action, cognition and their relationships’ isn’t perception, action, cognition, or their relationships.

The ‘Sagan standard’ (by Carl Sagan) is a heuristic relating to the burden of proof: ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence’. It is quite clear now that Predictive Processing involves making some quite enormous leaps. Is the fact that a paradigm cannot explain something, really a good enough reason to conclude that thing doesn’t exist?

The problem here is that we find ourselves drunk on a new idea, and ‘Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.’[3]

[1]https://predictive-mind.net/epubs/vanilla-pp-for-philosophers-a-primer-on-predictive-processing/OEBPS/01_WieseMetzinger.xhtml#:~:text=It%20is%20not%20directly%20a,2011%3B%20Bastos%20et%20al.

[2] Bennett, M. R., & Hacker, P. M. S. (2022). Philosophical foundations of neuroscience. John Wiley & Sons.

[3] P. 28, Abraham Kaplan (1964). The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Co.

Nice Article. Some overreach with PP

However;

PP does not redefine knowing, understanding, or meaning.

It does not deny normativity or agency.

It does not replace epistemology or philosophy of mind.

It explains how subpersonal processes make perception and action possible.

I had an exchange of ideas with Wray on X, and the parallel he drew between AI hallucinations and human errors struck me as particularly flawed.

According to Wray, both hallucinations and errors are the result of a prediction gone wrong. However, AI hallucinations are responses as valid as any other (essentially a roll of the dice that turned out one way rather than another), whereas human errors are, well, errors. Hallucinations only reveal themselves as such if an external observer judges their adherence to reality; they are not inherently 'faulty' in themselves. In human errors, one can usually reconstruct where the reasoning went astray (a false analogy, a miscalculation of proportions, forgetting a variable or an element of the logic, swapping digits or names, etc.).

For me, this was enough to reject his hypothesis.